7 lessons from dyke economies 💰👭

honoring Jewel Thais-Williams and the organizers of Dyke Day LA

Hello to the 5,253 hotties who subscribe to this newsletter! Thank you for being here.

For those of you who are new here, let me reintroduce myself: I’m Leo 👋 By day, I’m a financial coach serving queer and trans communities across the US. I also teach personal finance from an anti-capitalist lens at colleges, workplaces, and nonprofit organizations.

In addition to running Queer & Trans Wealth full-time, I am also a freelance writer and independent journalist.

This summer, I had the pleasure of writing two stories for the LA Public Press:

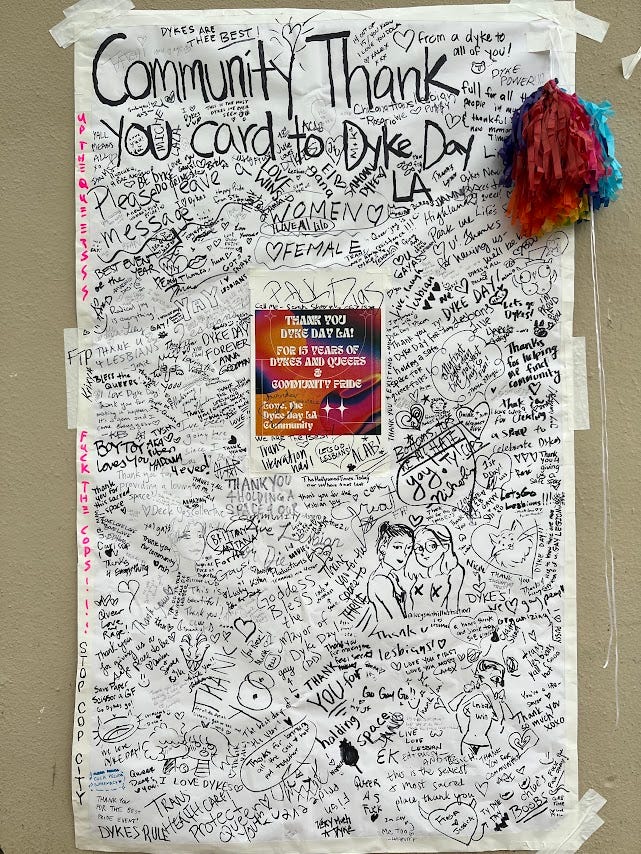

In June, I wrote about the 17-year history of Dyke Day, a free event in Los Angeles that features drag, burlesque, kink, community care resources, kid-friendly activities, leg wrestling, free pap smears, a senior tent, and so much more. In contrast to the commercialized version of Pride that happens in West Hollywood, centering able-bodied gay men with abs and charging $20 cover fees for parties, Dyke Day prides itself on keeping the event free, accessible, and cop-free.

In July, I wrote about Jewel Thais-Williams, a queer Black entrepreneur who owned and operated an iconic nightclub called Jewel’s Catch One from 1973 to 2015.

In the 80’s and 90’s, Jewel hosted fundraisers for queer and trans folx with HIV at her iconic nightclub. She co-founded an organization called the Minority AIDS Project to inform Black and Latinx folx about HIV. She used the profits from Catch One to start a housing project called Rue’s House, named after her wife, for women and children affected by HIV. In 2001, she went back to school to study Chinese medicine. She opened a free/low-cost acupuncture clinic called the Village Health Foundation right next door to the bar. By 2020, the clinic had served over 20,000 clients, according to Suite Life Concierge Magazine. At one point, Jewel owned and operated a vegan restaurant, in addition to running a bar and an acupuncture clinic.

I’m exhausted just reading those paragraphs about Jewel — I truly have no idea how she did it all, and neither do her mentees and loved ones who spoke with me after her death.

She died on July 7 at the age of 86. I had the honor of attending her memorial, where the mayor of LA declared Catch One a historical landmark. I have never seen so many Black and Brown queer and trans folx of all ages in one place, celebrating such a beacon of our community. This memorial was truly one of the best parts of my summer.

Pulling from the research and interviews from these two articles, plus experiences in my own financial coaching practice:

Here are 7 lessons I learned about money & business from dyke economies

🤝 I’m still accepting 1:1 clients. For more information about my services, please reach out at hello@queerandtranswealth.org.

👨🏫 Hire me to teach! In the past, I’ve taught at institutions like Northwestern University, Iowa State University, UC Berkeley, and California State University, Los Angeles. I’ve also given workshops to workers and community members at orgs like Folx Health and Nodku Therapy Group. If you’re interested in hiring me to speak or teach, please fill out the form on this page.

1. Dykes are spiritual AF

In my financial coaching practice, I noticed that so many of my clients have a spiritual practice that anchors them in times of financial uncertainty. I thought to myself, “We’re all on the same algorithm, and I’m also spiritual as fuck. Makes sense.”

I was pleasantly surprised to learn that our spiritual tendencies extend beyond social media algorithms and trendy astrology.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Jewel’s sister, Carol Amos, and activists that Jewel mentored for 20-30 years. They all told me the same thing: Jewel had a rigorous spiritual practice, and she spoke openly about it. She was a member of Alcoholics Anonymous and hosted meetings at Catch One. In a 2016 documentary called “Jewel’s Catch One,” Jewel said that she took her sobriety so seriously that if running Catch One got in the way of her staying sober, she would close the club.

Amitis Motevalli, director of the William Grant Still Arts Center, which serves community members ages 0 to 108, said about her mentor of 20 years, “She talked openly about moments she had with substance abuse, et cetera. That’s what really made you connect: the fact that she was so humble, never placing herself above anybody.”

Another mentee named Jeffrey King, who founded In the Meantime Men’s Group, said, “One of her sayings, as she got older, she repeated it more, is that she wanted to return to the Ancestors empty.” Her sister, Carol, added, “She said she would [return to the Ancestors] with her suitcase empty — that she would have given away every single gift, every bit of knowledge, inspiration, and encouragement, love and compassion. And that’s what she did. I believe her suitcase was empty.”

2. We create economic opportunities for our friends… and it comes back tenfold

While working on this article, I also had the pleasure of meeting an actor and artist named Charles Reese, who frequented the bar in the 80s and 90s. “I think I experienced that club for the first time in 1987,” he said. A year later, Jewel rented Catch One to a production company that was making a film called Tap starring Gregory Hines and Sammy Davis Jr. Coincidentally, Charles was hired as an extra for that film.

He said, “Here I am in a place where I was dancing. Now I’m an extra on set. The fact that she could use her club, not just as a dance club, but also, a business transaction. She had to get on the registry to have that club available.” Charles would later become one of Jewel’s first acupuncture patients at the Village Health Foundation.

On the surface, Catch One was a place to let loose, explore your identity, and find joy with other queer and trans people of color. Beyond the parties, Catch One was a Black economic hub that provided work and exposure for artists, DJs, bartenders, and more.

In a documentary titled “Jewel’s Catch One,” released by Ava DuVernay’s production company Array, a DJ named Bobby Martin said, “I owe her a lot for jumpstarting my career.” Martin said he used to sneak into the club when he was 17. As an adult, he worked there from 1980 to 2015. In the documentary, he said, “The 80s and 90s were very good to me. I made a lot of money because of her.”

Fast forward to now: Out of all the demographics of folx that I serve as a financial coach, dykes are consistently thinking of the big picture. Dyke entrepreneurs and workers are not just thinking about how they can personally benefit from a new venture or financial opportunity — we also think about how our work will uplift others.

3. Revenge is a potent motivator

In 1973, Jewel worked at a supermarket across the street from the bar that used to be Catch One. Amitis told me, “She was walking home trying to get a drink right around where the Catch is. She was going to a bar, and the bar said, ‘No Blacks. No gays. No dogs.’ [Catch One] was her revenge plan long-term.”

In a 2017 interview with Outwords Archive, Jewel said she bought the Catch One with a $1,000 down payment. *cries in millennial at that number* She had 30 days to raise another $17,000, and she had no idea how she’d do it — but she found a way.

For Jewel, the key to building her wealth was to tap into that righteous anger and let it become fuel for her larger vision.

4. Entrepreneurship is just another job ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

When asked about being self-employed in Outwords Archive, Jewel simply shrugged and said, “I knew that being self-employed for me was my only choice. I didn’t want to work for anybody for the rest of my life.”

Her first business opportunity was to open a dress shop with her sister, Carol. In the Outwords interview, she shared the wisdom that entrepreneurship is just another job. Being your own boss does not make you better or worse than anyone else — it’s just another way to make money.

In my financial coaching practice, I learned that

5. DIY-K-E work ethic makes the world go round…

C. Fitz, who directed the documentary “Jewel’s Catch One,” said, “Jewel’s work ethic was always clear. She led by example.” Jewel took pride in waxing the floors of Catch One in the early days of the club. Fitz said that, during the celebration of her selling the club, “Somehow she was everywhere until she closed her eyes each night to rest.”

Jewel’s sister Carol added, “There’s probably many days where [people were] partying until 5 o’clock in the morning and the clinic needed to be open at 9 or 10 o’clock, and she was there giving acupuncture treatment.”

Similarly, when I interviewed the organizers of Dyke Day, I learned that they have been able to keep my favorite event of the year free because it operates on a gift economy, a system of exchange based on generosity, where goods and services are given freely. Gift economies have been used by Indigenous cultures and spiritual communities for centuries to support community gatherings.

Dyke Day has two fundraisers before the main event to raise money for performers and permits. Outside of that, Dyke Day exists thanks to organizers and volunteers who give their labor for free, knowing how much our community needs these spaces.

Attendee-turned-organizer Vanessa Craig said, “It’s straight up DIY-K-E. People are so down with this mission, with this space, with this creation that has gone out of control in the most gayest, beautiful-est way, that people just want to be a part of it.”

6. …but workaholism and burnout are also prevalent in Dyke culture 😓

In the documentary “Jewel’s Catch One,” Jewel’s wife Rue complained about her never-ending work commitments. Rue lamented that Jewel had a hard time taking much-needed breaks from her work so that they could take vacations together.

On the other hand, Dyke Day organizers said that they keep a rotating, non-hierarchical organizing committee to avoid burnout. However, the times that we live in and the injustices we face ask too much of each individual organizer. Regardless of organizing structure, burnout seems inevitable.

7. Dykes prioritize accountability before profit

I asked Jewel’s mentees what lessons she would have wanted to pass down to young queer communities of color:

Amitis said, “Queer people of color in community, there’s a lot of backbiting. And that’s the one thing she definitely did not tolerate. She wouldn’t mess around with us. She just cut the gossip and everything. She’s like, ‘I don’t care if you like so-and-so. It doesn’t matter. Community comes first.’”

Jeffrey King, who was mentored by Jewel since the 90s while working on the Minority AIDS Project, said, “Community can be a little messy. There’s just a lot going on and unresolved, unhealed stuff. She was a master navigator at dealing with people who had been deeply wounded. I’ve never really seen a lot of people who have that gift.”

Amitis added that Jewel had a group of friends whose opinion she trusted to keep her accountable. “All her life, she always had humility. She would get checked because she kept people around her that reminded her what needed to be in place.”

Similarly, when I asked the organizers of Dyke Day what advice they had for others who want to organize free, values-aligned events, they said accountability over profit was key.

OG organizer Lynn Ballen said, “We try so hard to be broadly, generationally spread out, so that when you come to Dyke Day, you see all different kinds of dykes. That’s the whole point. It’s also dykes of all genders, that’s super important to us. It’s deeply part of our identity. And of course, no cops and no corporate sponsors.” These values were shaped over years of listening to attendees and collaborating with them to co-create activities and spaces that meet their needs.

Vanessa said, “People who have maybe done grunt work one year get to shine in a different way in another year. It’s a very intuitive, Tetris-type of thing where it takes somebody who’s been doing it for a while to see these nuances and share them with the rest of the team.”

Dyke Day’s organizing committee is non-hierarchical with collective decision-making processes. They talk through decisions thoroughly to make sure the group’s intentions match their impact, and to hold each other accountable when harm happens.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you so much for reading this newsletter! Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to keep this effort going <3

Also! Big shoutout to my editor, Michelle Zenarosa, for commissioning these pieces for the LA Public Press! <3 Thank you, thank you, thank you!

This was such an educational and INSPIRING read. I have a new found hero in Jewel and now Dyke Day LA is on my Bucket List. Thank you Leo!